Last month, Harry Styles’ third solo album Harry’s House brought home the coveted Grammy for Album of The Year, beating Beyoncé’s Renaissance, the frontrunner (and many would argue deserved winner). The hate pile-on began almost immediately with tweets joking about a race war and comparing Styles’ victory over Beyoncé to the electoral college vs. the popular vote. That night on Twitter echoed summer 2022 with the much-covered press tour of Styles’ film Don’t Worry Darling, a psychological Stepford Wives-esque thriller, where Styles plays the film’s leading man. In addition to press and hate directed at his then-girlfriend, the film’s director, Olivia Wilde, multiple articles appeared eviscerating his acting abilities. This derision was mirrored on the internet as the Twitterverse gleefully picked apart promotional clips from the film, mocking everything down to his accent. In the aftermath of Styles’ Grammy win, several people announced unambiguously that Styles’ music is midling, calling it “generic, boring” and “serviceable Uber music.” Music publication Pitchfork pulled no punches in their review of Styles at the awards show. Writer Sam Sodomsky, derided the “Gap-commercial choreography” in Styles’ performance, calling it “boring—the very quality Harry Styles works so hard to convince you he’s not.” These critiques of Styles’ work are more than valid, especially as he quickly rises through the music industry’s ranks. But, in each of Styles’ quasi-scandals, there seems to be a glee in critique that stands in stark contrast to the years he seemed untouchable, swept up in the internet’s “smol beanification” of grown-ass men. With the outcry after Styles’ controversial Grammy win and Don’t Worry Darling’s disastrous press tour, it’s almost as though the internet had been perched on the edge of its seat for an opportunity to give him a platform-wide flogging.

I don’t find Styles’ music nearly as fascinating as his celebrity. And despite his mainstream success, to me, Styles will always be a social media star. The distinction of “social media star” vs. “normal celebrity” may feel useless today. (Almost) every major star has a social media presence, stans, memes, and at least a couple of viral moments under their belt. But One Direction, alongside Justin Bieber, was one of the first major acts championed by a generation raised on the internet. The new rules, possibilities, and avenues for celebrity performance were being written in real-time by One Direction and their fans. However, this doesn’t mean they started from scratch. Performance of self isn’t new among the famous, mimicking our own modulation of self-presentation depending on our environments, except with heightened stakes.

Sociologist Erving Goffman located two spheres of self: the curated public facing persona and the person we become in private. In their book Celebrity: A History of Fame, Susan J. Douglas and Andrew McDonnell describe these spheres as “front stage selves” and “backstage selves,” respectively. A key distinction between the front and back stage selves is the presence of “ungovernable acts” or “behaviors that can disrupt our performance and that we must control.” This can encompass everything from burping to rolling your eyes, essentially any social faux pas. Navigating this duality seems easy enough, but, media scholar Joshua Meyrowitz argued social media opened up a third stage. Douglas and McDonnell call this “the side stage” which “may appear casual and unregulated, certainly less polished than the glittering front stage, [although] the performance of self in this region is actually carefully curated as well.” A hallmark of the social media age, the side stage represents expectations that celebrities be relatable and provide in-depth access to their interior lives—not in a way that negates their front stage persona, but translates or builds on it in a backstage setting.

The side stage is encapsulated in the video diaries Styles participated in as a member of One Direction. While the group was still competing on The X-Factor, they would take fan-submitted questions, answering them while sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on a stairwell, and staring directly down the barrel of a camera lens, at the viewer beyond. There were inside jokes, pranks, fits of laughter, and mishaps, all of which supported the public understanding that these five boys who never met before auditioning were best friends. These moments were replicated in the band’s live shows where the boys would goof off and pull fun, wholesome pranks, like pantsing each other. The sum of their public image encapsulates the essence of nostalgia with so-called bad behavior distilled into harmless teenage kicks. At every turn, joy and young-adult liberation are at continuous high, without a trace of any negative undertones. It’s simply five young, pretty boys having the time of their life. With such a vibrant, softly anarchic image, how could hordes of young people not fall for these cute troublemakers, these sensitive rebels?

While social media’s juxtaposition of celebrities and regular people on a single feed may spark toxic comparison (more on this later), it also begets a sense of control. Coming in third, The X-Factor didn’t cement One Direction’s fame as much as the interest they generated on platforms whose rise coincided with their debut. Fans’ ability to find them via YouTube, Twitter, and Tumblr, translated into tangible social capital for the band. During their first American tour opening for Big Time Rush, they received more fanfare than the headlining act. The internet offered a central hub of myth-making, building on the legacy of boy bands as abstract concepts, presenting a non-threatening ideal of manhood for young girls’ projection. Fanfiction, video edits, and memes could be constantly disseminated, turning celebrities into bottomless hubs of content (even if they themselves were not putting it out). In this glut of material, it’s easy to apply a faux depth to a celebrity’s internal being. Even if you have seen every photo of Harry Styles, you haven’t seen them in this edit, in this order, against this background music, and maybe that combination could illuminate some new dimension to your understanding of him. More importantly the internet also offered validation of internal feelings that, at a large enough scale, can spawn a intra-group consensus, later mistaken as fact. If an entire community of people can get behind an idea or share an impulse, even if it’s through conspiratorial thinking, doesn’t that make it at least feel credible? While fandoms have all the capacity in the world to be life-affirming, positive communities, no one truly understood during those early years of One Direction how the internet could magnify fan (and hater!) power on a truly destructive scale—a fact that now seems obvious.

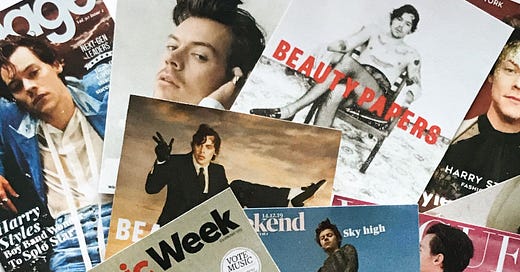

Seven years have passed since One Direction split, but looking at the finer details in Harry Styles’ highly successful solo career, it almost feels like he never left the band. Yes, his songs allude to sex in ways that he could not in One Direction. His vibrant vintage style flirts with androgyny enough to anger Fox News viewers and men’s rights activists. On the surface, Styles seems entirely reinvented, but is he? Are his choices really that culturally daring? The people who claim he’s ruining masculinity are the same people who threw a hissy fit about a desexualized M&M cartoon, so it’s not like they are hard to outrage. Many have pointed out Styles is not the first man to wear a dress, and much of his “controversial” wardrobe is plucked from Alessandro Michele’s turn with Gucci, a storied fashion institution. Styles generally refrains from using social media in a personal capacity, reserving it for professionally shot (and undoubtedly curated) photos from his tour alongside promos for his upcoming projects. Much like in One Direction, his concerts provide an opportunity for him to banter with fans, giving them a “backstage” glimpse into his personality but in a “front stage” environment. At every juncture, his public image is controlled with truly “ungovernable acts” coming few and far between.

This tension between Styles’ public self and private world translates into his music. One critic, Cyrena Touros, who reviewed Harry’s House, noted that Styles borrowed sonically from Golden Age rockstars while plugging them into a front loaded album structure reminiscent of One Direction. Ultimately, she concluded the album lacked a point of view. “Inside Harry's House, nothing feels all that new or urgent, good or bad” Touros wrote, adding that Styles seemed afraid of mining the darker parts of himself for the album. Previous songs of his have touched on intense jealousy, but, he doesn’t seem interested in “exploring his possessive nature — or indeed, any petty or immature behavior — in anything other than offhand, past tense ruminations.”

Another review of Harry’s House, from The Washington Post concurred with Styles’ inability to reveal the less likable parts of himself in his songs, writing “Most of the things he admits to enjoying are the usual Internet Boyfriend things no one could reasonably object to: riding bicycles, the occasional edible, sexy time by the beach, hash browns with maple syrup. There are careful references to cocaine, but they seem wedged in, as if somebody in marketing thought Styles should have a vice.”

I do not know Harry Styles: The Person, only Harry Styles: The Brand, and cynically, in the context of a brand, this all feels profoundly synergistic. It feels designed, dare I say calculated, to produce a persona that isn’t so much likable as it is unhateable. Styles earned a mass audience in One Direction, and it seems he’s doubled down on maintaining that. All this isn’t to say that this current iteration of Harry Styles can’t be important or meaningful to his fans— the opposite, in fact. Styles is doing just enough to differentiate himself without truly alienating the general public. He remains a viable commercial product, and just as much of a blank vessel for others’ projections as he was in his boyband days.

Perhaps my cynicism is (pardon the pun) a sign of the times. In the celebrity world and socializing in general, people continually evaluate how others perform their front-stage self, or, as Goffman writes, “check upon the validity of what is conveyed by the governable aspects.” The shifting nature of the internet has drastically changed the lens through which we judge others, but especially celebrities. In 2010, a larger public may have been able to wholeheartedly believe that One Direction’s friendship was pure and everlasting. That their video diaries were genuine reflections of themselves, instead of a calculated PR move. According to New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino, the tipping point of the internet came in 2012, at the height of One Direction’s popularity. With the shift from Web 1.0 to 2.0 came a loss of belief that the internet could be a site of genuine self expression. “The dream of a better, truer self on the internet was slipping away. Where we had once been free to be ourselves online, we were now chained to ourselves online, and this made us self conscious,” Tolentino wrote in her book Trick Mirror. “Because the internet’s central platforms are built around personal profiles it can seem — at first on a mechanical level, and later on as an encoded instinct—like the main purpose of this communication is to make yourself look good.”

In other words, our belief in the side-stage waned considerably if not died entirely. The idea of authenticity seems foreign on social media—even if it’s what platforms are ostensibly designed to promote. It’s easy to assume self-presentation in the internet age always has an agenda, prompting fans to pick apart social media posts, song lyrics, body language, and outfits. We know now, after members of the band spoke candidly about their experiences, that life in One Direction was not as carefree as it seemed. There were backstage fights as well as mixed feelings about contracts and creative control. Trust in front-facing narratives further eroded with the fall from grace of seemingly wholesome celebrities like Bill Cosby. The success of the #FreeBritney movement, and Taylor Swift’s infamous easter eggs, while radically different in tone, feel like a nail in the coffin— proof that conspiracy, no longer on the fringes, is now an assumed language between stars and their fans. Conspiracies have even overshadowed Styles’ fandom (known as Harries), some of whom believe Styles is a victim of a plot by management to keep him in the closet, alongside his former bandmate (and alleged secret love) Louis Tomlinson. Called Larries, these fans believe Tomlinson’s child is fake and that every heterosexual relationship Styles and Tomlinson have are PR stunts. An act as small as Styles’ wearing a blue bandana can be considered an implied declaration of love for Tomlinson. This thinking supposes that celebrity and fan are operating on the same granular level, imbuing every word and visual frame with secret significance, assuming apparent meaning and true meaning never fully align.

This cynicism can act as a guard against the inferiority complex that social media inherently infects its users with. In the philosophy YouTube channel Contrapoints’ video on envy, creator Natalie Wynn notes that “envy is not just wanting what someone has, it’s begrudging them what they have. You might even hate the person you envy and want them to lose what they have, to be humiliated and destroyed even if their downfall doesn’t benefit you.” Wynn cites social media as an “incubator” for envy because it encourages comparison and puts a target on the backs of public figures whose highly curated, glamorous lives are especially visible. But envy also seems to be a yearning for a kind of control, that’s at least moral if not material. Although envy is deeply personal, collective envy and the collective shaming it inspires, polices the sin of exceptionalism. But because admitting envy would mean admitting one’s inferiority, envy can stay hidden until it finds the perfect Trojan horse. Wynn notes envy is usually sublimated into “ego-defending” rationales, creating controversy even when it doesn’t exist.

On the one hand, there has always been a cohort of incels and misogynists who despise Styles for his female following as well as his fans for their freedom of expression and cultural power. On the other, envy is an understandable reaction to the inflation of Styles as a kind of godlike figure. According to stans, at 26-years-old, Styles was allegedly being “groomed” by 36-year-old Olivia Wilde and held hostage by his team. He is beautiful and kind, only a victim, never a villain, to a degree verging on sainthood. But if Styles truly lived up to the mythos that surrounds him, what does that mean for the rest of us? Why is it that everything Styles does make headlines, while others tirelessly jockey for even the smallest sliver of social media fame? This is all exacerbated by the obvious advantages Styles’ gets from being a conventionally attractive, cis, white, male—a privilege demonstrated in his ability to win an Album of the Year award from the Grammys, which has consistently passed over deserving Black artists.

Styles’ turn in Don’t Worry Darling offered the perfect opportunity for envy to strike. Acting dares others to see you as someone other than yourself. By trying to inhabit the role of an incel who had trapped his girlfriend in a 1950s simulation, Styles needed to break the mythos that had defined his career and sheltered him from scrutiny. Failure is arguably one of the most quintessentially human traits, and to many, including myself, Styles’ performance in Don’t Worry Darling indicated he was in over his head. This misstep offered an outlet to critique Styles on reasonable grounds while actually expressing the more personal frustrations he provoked. Like his acting, Styles’ controversial Grammy win for Album of the Year held his work up to a higher bar, inviting comparison against him, and illuminating the privileges of white, male identity that can edge mediocrity over the line to beat industry changing works from Black women artists. In both instances, the internet offered fans an opportunity to remind Styles that the audience was still the boss and could tear him down as easily as they built him up. Performers may have the money and talent, but the public, with the unwieldy weapon of social media at their disposal, remains the well of celebrity’s most covetable currency: social capital.

Image source: Pinterest.